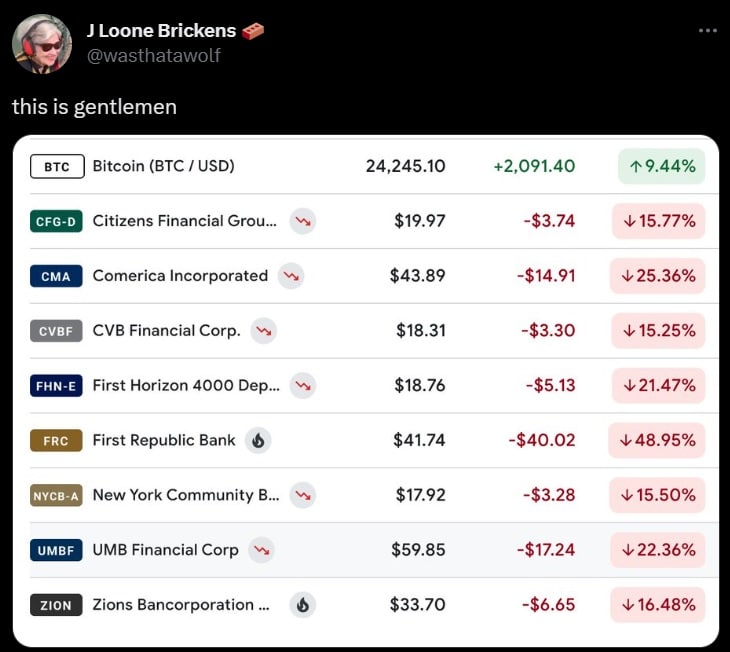

Since Silicon Valley Bank became insolvent and Signature Bank was shut down, bitcoin has been on the rise.

- Bitcoin has risen from USD 19,900 to USD 26,000 in just a few days

- Bitcoin glitters in the face of the prospect of systemic risk in the banking system.

Just a few days ago, the commercial institution Silicon Valley Bank filed for bankruptcy. The bank had approximately USD 209 billion in financial assets (mortgage and treasury bonds) and only about USD 175.4 billion in liquid deposits, rendering it insolvent in meeting the withdrawal demands of its users as a result of the banking panic.

Silicon Valley Bank was preceded by Silvergate Bank and followed by Signature Bank. Today, many US citizens and businesses are afraid of not getting the cake that they thought belonged to them, but was only theirs for the taking. A sense of systemic risk pervades the American banking climate.

What you didn’t know about the banking system

Remember the last time you opened a bank account? The aseptic and impeccable atmosphere, the columns and the wood of the gleaming desks, the human decency dressed in suit and tie, and the feeling of being in a cold and comfortable aeroplane cabin.

You felt grown up, grown up, important: it’s your first account or one more of your various bank accounts. It doesn’t matter: that’s why you were there that day, solemn. The business advisor hands you a set of papers, which you sign without paying much attention, savouring in advance the facilities of your new account. And that’s it. You’ve enjoyed its benefits for years.

One day, unexpectedly, your ‘trusted’ bank goes bust, and the bank contact assures you that you will be reimbursed. Months go by, but nothing happens. What happened to your money, to your money, where is your hard-earned money?

Maybe you forgot to read the fine print of the contract you signed. Let me explain: once you deposited your money in that account, it was no longer exclusively yours. It would be technically correct to say that, since then, your money is owned by two people at the same time. You and the bank, or you and an unknown borrower.

Of course, when you check your account, the amount of your savings remains the same. You don’t have a dollar more, but you don’t have a dollar less in your balance either. “What do you mean it’s not mine, when I can see it in my account and withdraw it whenever I want,” you say. Well, that numerical amount you see in your account is a nominal amount; in other words, it’s a figure that represents how much you’ll get when the pie is shared out, not how many pieces you actually have.

In reality, the bank may be shopping with your money. It is likely that, unbeknownst to you, you are financing their business ventures with the money you deposited with them ‘for safekeeping’. That makes you not a customer, not a saver. Put bluntly, that makes you a lender. It turns out that the bank is not doing you a favour; you are doing the bank a favour by lending it money.

That the bank uses your money to buy things is possible because the current financial system allows the application of the so-called «fractional reserve». Through this method of using deposits, banks are not obliged to keep 100% of their customers’ funds in reserves.

This means that if the amount of money that a certain number of customers wish to withdraw is greater than the bank’s current reserves, the bank will not be able to give out everyone’s share of the pie. Someone will be left without theirs: it could be you, someone else, or the bank itself if it decides to liquidate its assets, go bankrupt and pray for a central bank bailout, which inevitably ends up causing currency inflation. Someone always loses.

In your case, you could withdraw your share, as long as the crowd does not think of withdrawing the money at the same time as you. You will be able to take back your share as long as there is no banking panic event.

What about Bitcoin? It has risen more than 20% since the news of the bank run spread, from USD 19,900 to USD 26,000, rejuvenating itself, vampire-like, with the blood of traditional banking. Other cryptocurrencies are also accompanying the bullish rally, being possible to observe, temporarily, a de-correlation of these with banking stocks and indices. This is a very different story to that of banking shares, with losses of up to 60% in a matter of hours.

Origin of the fractional reserve

The origin of the fractional reserve can be traced back to the birth of the first banks to issue paper money. These banks, which were founded in 1609, issued their own coins to be used as currency.

Thus, in the mid-19th century, the printing of currency by banks led thousands of institutions to start issuing banknotes, giving rise to the existence of more than 8,000 different types of banknotes issued by private banks and companies. A practice which, when the bank failed, took its depositors with it. Thus, losing everything. This situation later led to a crisis that lasted from 1837 to 1843.

This crisis forced the rulers to adopt a new system that would guarantee a backing for the banknote, as well as stability and reliability so that the banknote could be used. This led to the creation of central banks. These banks were created with the intention of backing the currency they issue, and they are therefore the only ones that can issue it. Thus, they were the ones who had to respond to the value of the banknote.

In this way, they also introduced the fractional reserve system which, in the final analysis, made the central bank responsible for answering to the depositor.

How can the bank make the fractional reserve?

The bank has a number of products that, depending on the customer, serve to store, accumulate and make a customer’s savings profitable.

Among these products, the bank has, for example, products that, like the fixed deposit, keep the saver’s capital in the bank in exchange for a return on the capital, which we call profitability.

In this way, the bank pays this return to the saver, in exchange for a commitment in which the saver lends his or her capital to the bank, which must give a return for ceding it to third parties. All this, guaranteeing the reserve that, by law, they must have in their coffers.

Furthermore, the bank is only obliged to keep part of its current accounts in cash. That is why, if we go to the bank and claim a large sum of money, they tell us that we will have that money available in a few days. In other words, they don’t have it in physical form.

Source: CriptoNoticias

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the autor Paulo Márquez and do not necessarily reflect those of CriptoNoticias or EurocoinPay

Disclaimer: The information set out herein should not be taken as financial advice or investment recommendations. All investments and trading involve risk and it is the responsibility of each individual to do their due diligence before making any investment decision.